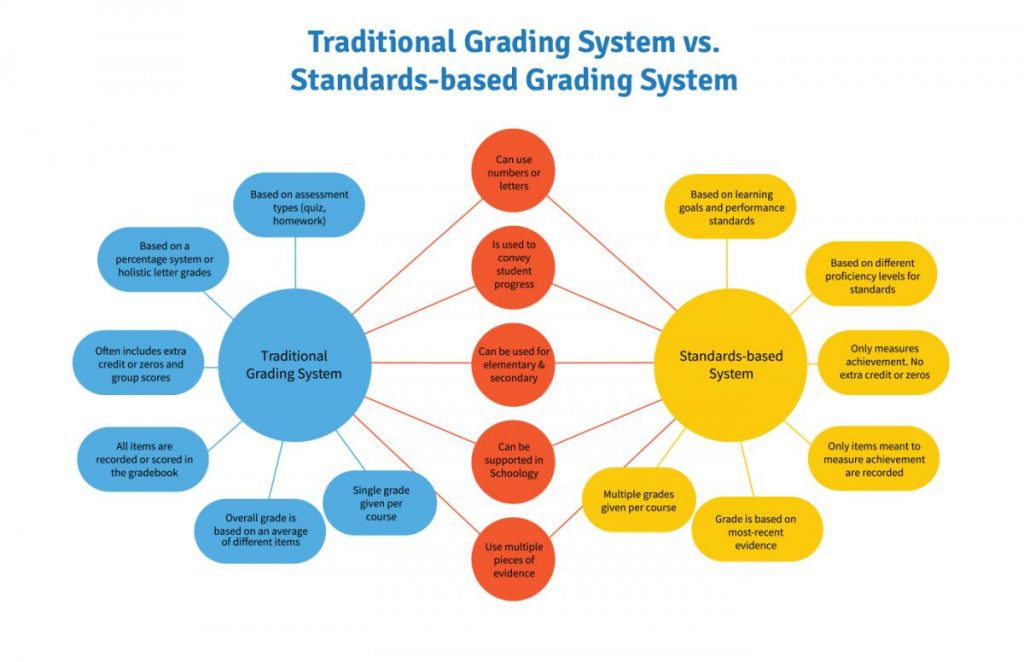

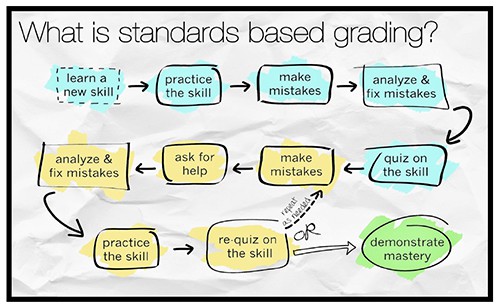

Standards-Based Grading (SBG) systems, while not really new to the world of education, have been gaining much more attention due to the current trends toward national “Standards-Based” Education. But what is SBG anyway? To begin our exploration, it may help to discuss what separates Standards-Based Grading from other kinds of grading systems.

Standards-Based vs. Traditional Grading

Standards-Based Grading is often contrasted with more traditional grading systems, in which students are given a grade for their performance on different assessments such as quizzes, tests, essays, and projects. These assessments are usually graded as discrete items, that is, separate quizzes will receive separate scores, as will separate tests, and separate projects.

Grades are often generated on a percentage scale, with 100% being the highest grade and 0% being the lowest. These percentages often correspond to the traditional letter grade system, which simplifies the 0-100 formula by giving students an A, B, C, D, or F based on ranges of performance. Sound familiar? This is probably the system that most people grew up being graded under. If this sounds logical enough to you, then why even consider other systems? What could another system have to offer? As it turns out, quite a lot. Let’s take a look.

The Traditional High School Grade Book

Now, I’m a high school English teacher, so I’m generally much more coherent when discussing things like this in the context of the discipline in which I work. Others have documented extensively what this could look like in other courses. Under the traditional system we’ve been discussing, here’s what an entry in a standard gradebook might look like (and indeed what my gradebooks used to look like):

Christina Kingston

- Personal Narrative: 78

- Romeo and Juliet Essay: 67

- Of Mice and Men Reading Quiz: 80

- Author Study Video Project: 85

Now, there doesn’t seem to be anything wrong with the gradebook above (besides the fact that Christina looks like she needs to shape up a little). However, a key shortcoming in this system emerges when we try to figure out how to exactly what Christina needs to do to shape up.

There is a failing score on the Romeo and Juliet Essay, for example. Well, what exactly does that mean? Did she not read the play? Did she read it, but not comprehend? Did the problem lie in the writing of the essay itself? If so, where? “What exactly needs to happen to help bring up the low grades up?” a parent might ask, for example. Well, I suppose we could ask the student, or even the teacher.

But what if the assessment was so long ago that neither can give us a sound explanation? And would a student be able to re-write an essay for a new grade? Under the traditional grading system, the answer has generally been “no.” And yes, while we see that she has earned a higher grade on her Author Study Project, what does that actually tell us? Where has she actually improved? It is in attempting to answer these kinds of questions that the need for an alternative reveals itself.

Grading to Standards

So what makes SBG so different from the traditional grading system?

Simply put, in an SBG system, students receive grades based on how they perform against agreed-upon standards of quality in different areas of performance. Here’s what part of a Standards-Based Gradebook might look like (which somewhat resembles what my gradebook looks like now):

Christina Kingston

- Use of Textual Support to Defend Ideas in Writing: Partially Proficient

- Ability to Summarize in Writing: Proficient

- Mastery of Grammatical Conventions: Proficient

- Mastery of Mechanical Conventions: Not Proficient

Now, not only can teachers see exactly where a student’s strengths and weaknesses lie, but the students themselves can as well (provided students have a way to track this information). In the most well-designed and executed systems I’ve seen, students have a chance to be reassessed on particular standards at later dates so that the gradebook always reflects a student’s current understandings, rather than the ones she displayed 3 months ago.

What this looks like in my classroom is the ability to resubmit essays that have been graded until a student (or administrator, or parent, or teacher) is satisfied with levels of performance in particular areas. Not many “one and done” assessments occur in my classroom because students are always growing and developing in their literacy skills and assessments should show that.

Under such a system, students can see exactly what they are learning (or should be) and how they are progressing, and student effort now has much more of a connection to student achievement. Students can now come to a tutoring session knowing exactly why they are there and what they need to accomplish before leaving. Teachers can remediate on particular skills and commend students on particular areas of accomplishment.

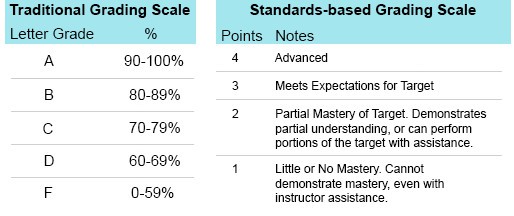

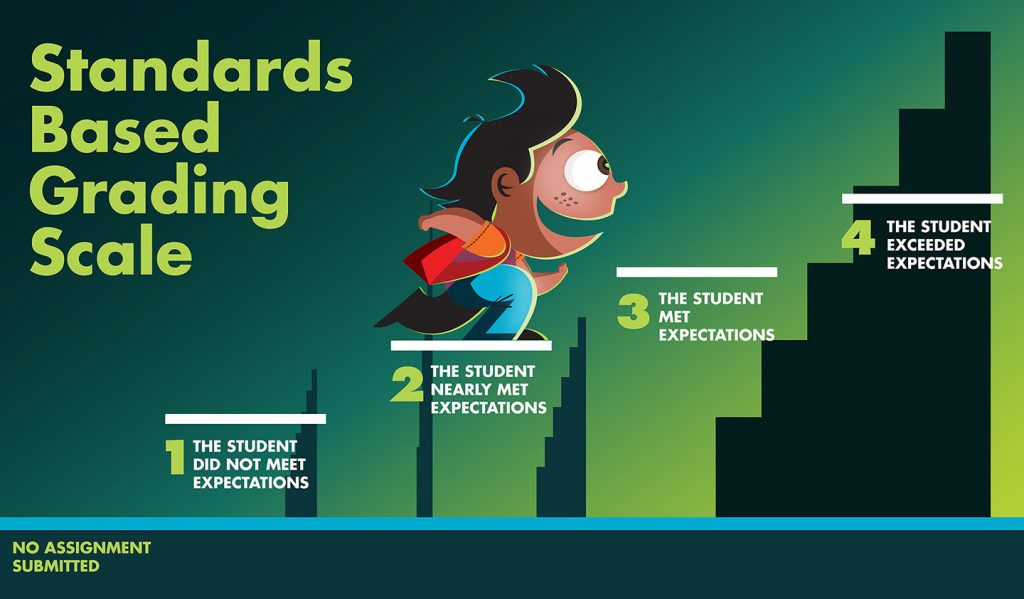

Levels of Performance

As demonstrated in the example above, SBG systems usually rank students based on four levels of achievement, sometimes assigning numbers to each level:

- 1: Does not meet standard

- 2: Partially meets standard

- 3: Meets standard

- 4: Exceeds standard

Particular flavors of standards-based grading vary, and although differing systems will use different labels, but the four ranks generally equate to the same levels of understanding. A “zero” in such a system would mean that a student has not even made an attempt to reach a particular standard.

Implications

This has several important implications for classroom practices. For one, gradebooks will probably have more grades than usual, and it may take a little extra time to get used to such a system, as well input the extra few numbers (or letters, or codes, or whatever it is you like to use). This is not as difficult as it sounds.

When grading according to a rubric, for example, you would simple enter separate grades for each area being measured on the rubric. And by now, we all know that rubrics should be aligned to “agreed-upon standards” rather than created according to teacher whim. Exactly what we mean by “agreed-upon standards” may require conversations about what students would be graded at classroom, departmental, and school-wide levels.

Also, giving students opportunities to have their work re-graded will undoubtedly lead to more time spent grading for teachers. For me at least, the trade-off is a much stronger feeling that the grade on a student’s transcript is much more connected to how they have demonstrated their learning. Finally, while this all may sound great in theory, different teachers will need to work out different ways to work the system into your current practices. Remember that your mileage may vary.

Standards-Based Grading, while not necessarily as radical a shift in grading methodologies as it may initially seem, very much requires a fundamental shift in the way that we as teachers think about grades. If it becomes clear to you upon reflection that traditional systems haven’t been painting the most complete picture of your students’ achievement, perhaps it may be time to consider the alternatives.