The summer months in temperate and tropical parts of the world bring crowds of human swimmers to lake and marine shores to cool off in the inviting waters. Unfortunately, these are the same waters frequented by wild water birds, many of whom are infected with blood parasites called schistosomes.

The lucky swimmers among us arrive at the beach or shore to find a sign: “No Swimming – Swimmer’s Itch.” If you see this sign, stay out of the water. Particularly when the water is warm, human swimmers are at risk of coming in contact with schistosomes and the consequences, though not dangerous, are very unpleasant—parasites in the water will mistake a human swimmer for a duck. Here’s the story of the bather’s malady called swimmer’s itch:

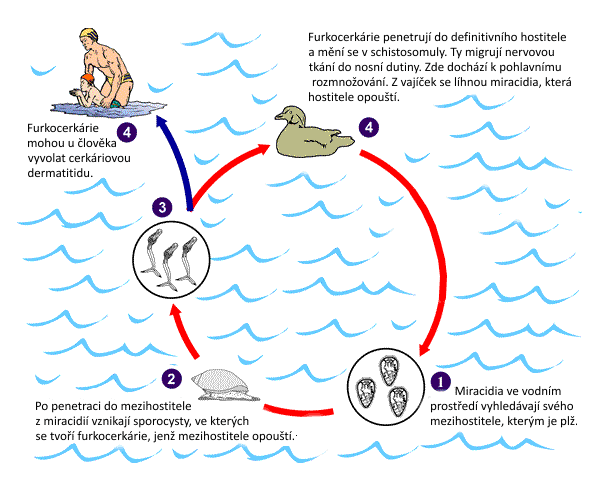

- Birds acquire the parasite when they visit water where schistosomes are present. These parasites are fortunate—birds are the hosts they are waiting for.

- The infective cercariae penetrate the birds’ skin and the parasites develop to adult worms in the avian bloodstream. When they are mature, the worms start producing eggs.

- Schistosome eggs are typically passed into water in waterfowl feces (life cycles of various schistosomes vary). The eggs hatch and the released larvae penetrate the bodies of aquatic snails.

- Inside snails, the schistosomes multiply asexually, producing many cercariae which are released back into the water. If water birds are swimming nearby, the cercariae enter the birds and start the whole process over.

- If, however, it’s human swimmers that are in the water, the cercariae will penetrate human skin. The swimmer often feels a prickling, burning sensation on the skin where cercariae are penetrating.

- If the human host has never been exposed to bird schistosomes before, it’s likely that nothing more will happen. He or she will soon forget the strange prickly feeling, and the tiny parasites will die under the skin—they cannot go any further because they are not in a bird.

- The second time a swimmer is in contact with avian schistosomes, the results are much more dramatic. Sensitized by the first exposure, the human immune system now launches an allergic reaction, producing an excruciatingly itchy rash and, frequently, pus-filled lesions at the site of penetration.

- The immune response kills the parasites again, but this time the swimmer must wait for relief as the rash runs its course. Subsequent exposures to avian schistosomes will result in the same miserable experience.

Surprisingly, swimmer’s itch is the least devastating of the schistosomes to burrow into human skin. Several species of Schistosoma cause serious human disease everywhere that they occur—but these are blood parasites of humans, not of birds.